Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

11 Feb 2025

A novel robotic reaching task to advance the assessment of approach-avoidance tendencies through kinematic analysisKayne Park, Matthieu P. Boisgontier https://doi.org/10.51224/SRXIV.446A novel Kinarm-based behavioral paradigm to probe reaching and avoidance actionsRecommended by Tarkesh Singh based on reviews by Michael J. Carter, Oindrila Sinha and Ana Gómez-Granados based on reviews by Michael J. Carter, Oindrila Sinha and Ana Gómez-Granados

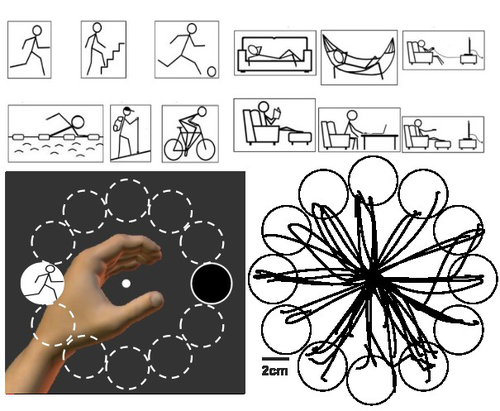

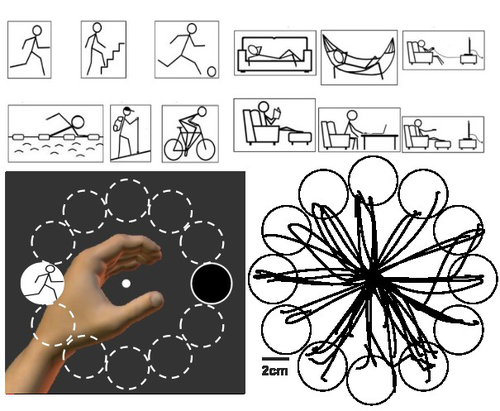

I recommend this technical report by Park and Boisgontier. The authors present an innovative adaptation of the approach-avoidance task using the Kinarm robotic platform. Their Kinarm Approach-Avoidance Task (KAAT) enables precise measurement of multiple kinematic variables across multiple reach directions, providing richer behavioral data than traditional keyboard or joystick-based approaches. The robust technical documentation, including detailed task specifications and pilot data, demonstrates Kinarm’s capability to capture nuanced aspects of motor behavior like reaction times, movement speeds, and acceleration patterns. Particularly noteworthy are the potential applications across various clinical domains. This work also complements previous work done by Perry and colleagues, where they used an object hit and avoid task to create a comprehensive statistical model of motor learning. The authors have also thoughtfully included the capability to apply resistive loads during reaching movements. The transparent sharing of materials and code through their GitHub repository also reflects commendable research practices. While the pilot sample is small, the thorough technical foundation laid by this work opens valuable new avenues for investigating approach-avoidance tendencies with a lot of kinematic detail. References

- Park K, Boisgontier MP (2025) A novel robotic reaching task to advance the assessment of approach-avoidance tendencies through kinematic analysis. SportRxiv, ver.2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Health & Movement Sciences. https://doi.org/10.51224/SRXIV.446

- Perry CM, Singh T, Springer KG, Harrison AT, McLain AC, Herter TM (2020) Multiple processes independently predict motor learning. Journal of Neuroengineering and Rehabilitation, 17(1), 151. doi:10.1186/s12984-020-00766-3

| A novel robotic reaching task to advance the assessment of approach-avoidance tendencies through kinematic analysis | Kayne Park, Matthieu P. Boisgontier | <p>The investigation of automatic approach-avoidance tendencies has traditionally relied on computer-based technologies that primarily characterise human behaviour through reaction times. However, these technologies are unable to accurately quanti... |  | Biomechanics, Exercise & Sports Psychology, Physical Activity, Sensorimotor Control | Tarkesh Singh | 2024-09-10 16:56:05 | View | |

05 Feb 2025

Cigarette smoke exposure as a potential risk factor for sleep problems in pregnant womenAleksandra Ciochoń, Łukasz Balwicki, Magdalena Klimek, Dariusz P. Danel, Anna Apanasewicz, Anna Ziomkiewicz, Andrzej Galbarczyk, Urszula M. Marcinkowska https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14777983Have you ever wondered about the relationship between active/passive smoking and sleep in pregnant women?Recommended by Géraldine Escriva-Boulley based on reviews by Silvio Maltagliati, Florian Chouchou and Jean-Philippe Chaput based on reviews by Silvio Maltagliati, Florian Chouchou and Jean-Philippe Chaput

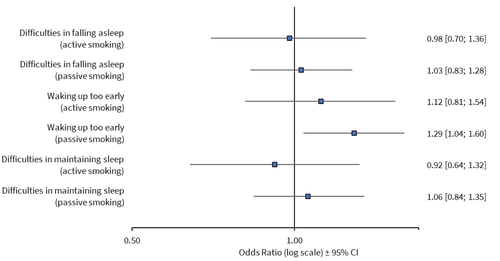

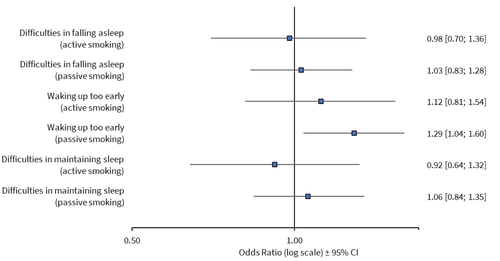

Pregnancy has been shown to affect the quality, duration, and pattern of sleep (Paavonen et al., 2017; Reid et al., 2017). These changes have important implications, as insufficient sleep is associated with health problems and complications during labor. In line with studies investigating the general population, a few studies focused on pregnant smokers and have also shown a prevalence of sleep abnormalities (e.g., Danilov et al., 2022; Lange et al., 2018; Paavonen et al., 2017). Studies examining the role of passive smoking on sleep are rare, be it in the general population or in pregnant women. The aim of the Ciochon et al. study was to investigate the relationship between active or passive smoking and three types of sleep problems during pregnancy: difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, and waking up too early. The authors hypothesized that pregnant women's exposure to smoking (active and passive) would increase their risk of sleep problems during pregnancy. Participants were part of a larger study: the Corona Mums project, which included 3365 pregnant women from Poland, aged 18 to 43 years. These women completed an online questionnaire during the COVID-19 pandemic, from May 2020 to September 2021. The authors conducted multivariate logistic regressions that included the following control variables: socio-demographic, pregnancy-related variables, and psychological variables. The results of the study showed that passive smoking is a risk factor for waking up too early, but they showed no evidence suggesting that active or passive smoking was related to any of the other sleep variables. The authors highlighted the roles of control variables included in the models. Specifically, sleep difficulties were related to age, place of residence, education, level of anxiety and depression in pregnant women, and the presence of nausea or vomiting. Further, in all the models, the level of anxiety, depression, and trimester of pregnancy (3rd trimester in comparison to 1st and 2nd) were significantly related to the risk of occurrence of sleep problems. While only one of the six examined associations showed statistical significance, the findings are still useful in highlighting potential risks associated with passive smoking and sleep disturbances during pregnancy. The study also underscores the need for more comprehensive investigations, including direct measures of sleep quality, such as actigraphy or polysomnography, which are necessary to better understand the underlying mechanisms and to confirm the potential impacts of both active and passive smoking on sleep during pregnancy. References

- Ciochoń, A., Balwicki, Ł., Klimek, M., Danel, D., Apanasewicz-Grzegorczyk, A., Ziomkiewicz, A., Galbarczyk, A., & Marcinkowska, U. M. (2025). Cigarette smoke exposure as a potential risk factor for sleep problems in pregnant women. Zenodo, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Health & Movement Sciences. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14777983

- Danilov, M., Issany, A., Mercado, P., Haghdel, A., Muzayad, J. K., & Wen, X. (2022). Sleep quality and health among pregnant smokers. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 18(5), 1343–1353. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.9868

- Lange, S., Probst, C., Rehm, J., & Popova, S. (2018). National, regional, and global prevalence of smoking during pregnancy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. Global Health, 6(7), e769–e776. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30223-7

- Paavonen, E., Saarenpää-Heikkilä, O., Pölkki, P., Kylliäinen, A., Porkka-Heiskanen, T., & Paunio, T. (2017). Maternal and paternal sleep during pregnancy in the Child-sleep birth cohort. Sleep Medicine, 29, 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2016.09.011

- Reid, K. J., Facco, F. L., Grobman, W. A., Parker, C. B., Herbas, M., Hunter, S., Silver, R. M., Basner, R. C., Saade, G. R., Pien, G. W., Manchanda, S., Louis, J. M., Nhan-Chang, C. L., Chung, J. H., Wing, D. A., Simhan, H. N., Haas, D. M., Iams, J., Parry, S., & Zee, P. C. (2017). Sleep during pregnancy: the nuMoM2b Pregnancy and Sleep Duration and Continuity Study. Sleep, 40(5), zsx045. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsx045

| Cigarette smoke exposure as a potential risk factor for sleep problems in pregnant women | Aleksandra Ciochoń, Łukasz Balwicki, Magdalena Klimek, Dariusz P. Danel, Anna Apanasewicz, Anna Ziomkiewicz, Andrzej Galbarczyk, Urszula M. Marcinkowska | <p>Abstract</p> <p>Cigarette smoking and exposure to cigarette smoke during pregnancy have detrimental effects on the health of expectant mothers, increasing the likelihood of respiratory diseases or infections. Due to the exciting effect of smok... |  | Health & Disease | Géraldine Escriva-Boulley | 2024-05-29 12:18:57 | View | |

09 Jan 2025

Improved accuracy of the whole body Center of Mass position through Kalman filteringCharlotte Le Mouel https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.07.24.604923Improved estimation of the whole-body center of mass, a step ahead in biomechanical analyses of balance control.Recommended by Jaap van Dieen based on reviews by Maarten Afschrift, Guillaume Durandeau and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Maarten Afschrift, Guillaume Durandeau and 1 anonymous reviewer

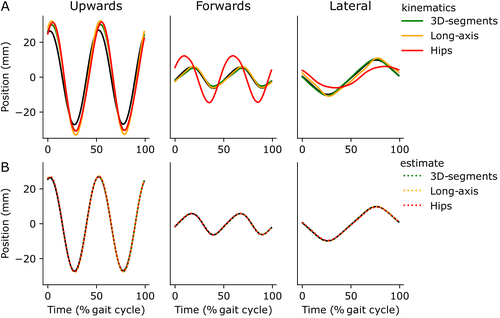

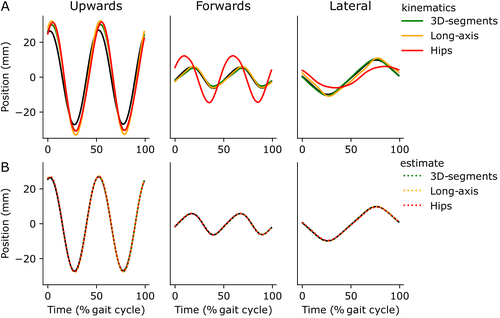

Estimation of the whole-body center of mass (CoM) is crucial in many biomechanical studies of human and animal movement. It is especially important in studies on the control of balance. For example, it has been assumed that sensory information is used to correct the horizontal position and velocity of the CoM (van Dieën et al., 2024; Wang and Srinivasan, 2014; Welch and Ting, 2008), to stabilize standing and walking against gravity. The studies cited have used more-or-less sophisticated estimates of the CoM, derived from kinematic, in some cases combined with anthropometric data, to predict motor outputs. These studies have provided support for the notion that the position and velocity of the CoM are controlled. This holds promise for the diagnosis of the quality of such feedback control as a cause of balance impairments and fall risk. However, such applications will suffer from errors in outcomes at the individual level, for example due to a poor fit of the anthropometrical model to a certain individual.

Le Mouel (Le Mouel, 2025) presents a novel approach to estimate the position of the CoM. The author proposes that CoM estimation can be improved by optimally combining kinematic and kinetic data through a Kalman filter. The Kalman-filter-based method was indeed shown to effectively addresses the inherent limitations of both kinematic and kinetic methods used in isolation. The author used an innovative approach to validate CoM estimates, based on incorrect CoM estimates violating Newton's laws of motion. The new method substantially reduced errors compared to conventional approaches based on kinematic (and anthropometric) or kinetic data only. The paper presents a clear and comprehensive description of the method and code implementation is provided such that the method can be easily adopted by colleagues in the field. The author also shows how the new method improves the analysis of stabilizing feedback control of walking, demonstrating the promise it holds for the analysis of balance control.

The method was tested on a small data set and further testing, preferably with participant pool showing large variance in anthropometrical properties, seems warranted. This may also lead to further improvement of the approach. For example, the anthropometrical model used could be refined by using regression equations that take into account segment circumferences of the individual tested (Zatsiorsky, 2002) or even by using individual imaging data. However, the proposed optimal combination of kinematic and kinetic data is likely to become a cornerstone of future methods for accurate CoM estimation.

References - Le Mouel, C., 2025. Improved accuracy of the whole body Center of Mass position through Kalman filtering. bioRxiv, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Health & Movement Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.07.24.604923 - van Dieën, J.H., Bruijn, S.M., Afschrift, M., 2024. Assessment of stabilizing feedback control of walking: a tutorial. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 78, 102915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelekin.2024.102915 - Wang, Y., Srinivasan, M., 2014. Stepping in the direction of the fall: the next foot placement can be predicted from current upper body state in steady-state walking. Biol Lett 10(9), 20140405. https://doi.org/ 10.1098/rsbl.2014.0405 - Welch, T.D., Ting, L.H., 2008. A feedback model reproduces muscle activity during human postural responses to support-surface translations. J Neurophysiol 99, 1032-1038. https://doi.org/ 10.1152/jn.01110.2007 - Zatsiorsky, V., 2002. Kinetics of Human Motion. Human Kinetics, Champaign, Illinois. | Improved accuracy of the whole body Center of Mass position through Kalman filtering | Charlotte Le Mouel | <p>The trajectory of the body center of mass (CoM) is critical for evaluating balance. The position of the CoM can be calculated using either kinematic or kinetic methods. Each of these methods has its limitations, and it is difficult to evaluate ... |  | Biomechanics | Jaap van Dieen | 2024-07-25 10:58:37 | View | |

20 Nov 2024

Cumulative evidence synthesis and consideration of "research waste" using Bayesian methods: An example updating a previous meta-analysis of self-talk interventions for sport/motor performanceHannah Corcoran, James Steele https://doi.org/10.51224/SRXIV.348Bayesian cumulative evidence synthesis and identification of questionable research practices in health & movement scienceRecommended by Wanja Wolff and Jérémie Gaveau and Jérémie Gaveau based on reviews by Maik Bieleke and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Maik Bieleke and 1 anonymous reviewer

Research is a resource-demanding endeavor that tries to answer questions such as, “Is there an effect?” and “How large or small is this effect?” To answer these questions as precisely as possible, meta-analysis is considered the gold standard. However, the value of meta-analytic conclusions greatly depends on the quality, comprehensiveness, and timeliness of the meta-analyzed studies, while not neglecting older research. Using the established sport psychological intervention strategy of self-talk as an example, Corcoran & Steele demonstrate how Bayesian methods and statistical indicators of questionable research practices can be used to assess these questions [1]. Bayesian methods enable cumulative evidence synthesis by updating prior beliefs (i.e., knowledge from an earlier meta-analysis) with new information (i.e., the studies that have been published on the topic since the earlier meta-analysis had been published) to arrive at a posterior belief - an updated meta-analytic effect size. This approach essentially tells us whether and how much our understanding of an effect has improved as additional evidence has accumulated; as well as the precision with which we are estimating it. Or to put it more bluntly, how much smarter are we now with respect to the effect we are interested in? Importantly, the credibility of this updated effect depends not only on the newly included studies but also on the reliability of the prior beliefs – that is, the credibility of the effects summarized in the earlier meta-analysis. A set of frequentist and Bayesian statistical approaches have been introduced to assess this (for a tutorial with worked examples, see [2]). For example, methods such as the multilevel precision-effect test (PET) and precision-effect estimate with standard errors (PEESE) [2] can be used to adjust for publication bias in the meta-analyzed studies, providing a more realistic estimation of the effect size for the topic at hand. This would then help to assess the magnitude of the true effect in the absence of any bias favoring the publication of significant results. Why does it matter for health and movement science? Open Science practices, such as open materials, open data, pre-registration of analyses plans, as well as registered reports are all good steps for improving science in the future [15–17] and might even lead to a ‘credibility revolution’ [18]. However, it is also crucial to evaluate the extent to which an existing body of literature might be affected by questionable research practices and how this might affect conclusions drawn from the research. Using self-talk as an example, Corcoran and Steele demonstrate this approach and provide a primer on how it can be effectively implemented [1]. By adhering to Open Science practices, their materials, data, and analyses are openly accessible. We believe this will facilitate the adoption of Bayesian methods to cumulatively update available evidence, as well as making it easier for fellow researchers to comprehensively and critically assess the literature they want to meta-analyze. | Cumulative evidence synthesis and consideration of "research waste" using Bayesian methods: An example updating a previous meta-analysis of self-talk interventions for sport/motor performance | Hannah Corcoran, James Steele | <p>In the present paper we demonstrate the application of methods for cumulative evidence synthesis including Bayesian meta-analysis, and exploration of questionable research practices such as publication bias or <em>p</em>-hacking, in the sport a... | Exercise & Sports Psychology, Meta-Science in Health & Movement | Wanja Wolff | Maik Bieleke, Anonymous | 2023-11-27 10:06:36 | View | |

19 Nov 2024

Structural vulnerability factors and gestational weight gain: A scoping review on the extent, range, and nature of the literatureJocelyne M. Labonté, Alex Dumas, Emily Clark, Claudia Savard, Karine Fournier, Sarah O'Connor, Anne-Sophie Morisset, Bénédicte Fontaine-Bisson https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3060015/v4Structural vulnerability factors and gestational weight gain in high-income countriesRecommended by Paquito Bernard based on reviews by Kelsey Dancause, Kadia Saint-Onge and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Kelsey Dancause, Kadia Saint-Onge and 1 anonymous reviewer

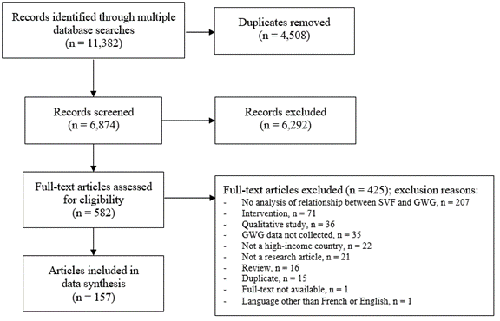

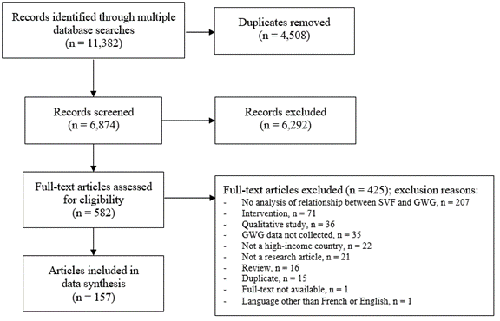

This manuscript presents a compelling scoping review examining the structural vulnerability factors associated with gestational weight gain. The topic is highly relevant because excessive gestational weight gain is prospectively associated with an increased risk of gestational diabetes and perinatal mortality. The authors employed excellent search strategies to address an area that is often overlooked, as structural vulnerability factors are generally understudied or not the primary focus in many existing studies. A total of 157 academic articles were included in the scoping review. The authors identified eight frequently studied structural vulnerability factors: race/ethnicity (58% of articles), age (55%), parity (31%), education (28%), income (25%), marital status (18%), immigration (12%), and experiences of abuse (physical, psychological, or sexual) (8%). Most studies were conducted in the United States of America, employed retrospective designs, and examined diverse populations in which a subgroup or the entire sample experienced one or more structural vulnerability factors. This work makes a significant contribution to understanding the role of structural vulnerability factors in gestational weight gain. It highlights the critical impact of systemic inequalities on the health of pregnant women and underscores the importance of addressing these disparities. Furthermore, the manuscript thoughtfully discusses the methodological challenges and limitations in the current literature, particularly in considering interacting structural vulnerability factors and social identities. From my perspective, this work provides a more detailed and nuanced analysis of structural vulnerability factors in the context of gestational weight gain than previous reviews. This review will undoubtedly serve as a valuable resource for clinicians and researchers, inspiring them to adopt an ‘intersectional lens’ in their future practices and research projects. Reference

Labonté JM, Dumas A, Clark E, Savard C, Fournier K, O’Connor S, Morisset AS, Fontaine-Bisson B (2024) Structural vulnerability factors and gestational weight gain: a scoping review on the extent, range, and nature of the literature. Research Square, ver.4, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Health & Movement Sciences. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3060015/v4

| Structural vulnerability factors and gestational weight gain: A scoping review on the extent, range, and nature of the literature | Jocelyne M. Labonté, Alex Dumas, Emily Clark, Claudia Savard, Karine Fournier, Sarah O'Connor, Anne-Sophie Morisset, Bénédicte Fontaine-Bisson | <p><strong>Background:</strong> Inadequate and excessive gestational weight gain (GWG) are rising epidemiological health concerns, affecting a substantial proportion of pregnant women in high-income countries and contributing to a multitude of adv... |  | Health & Disease | Paquito Bernard | 2024-05-03 23:40:07 | View | |

17 Nov 2024

Change in exercise capacity, physical activity and motivation for physical activity at 12 months after a cardiac rehabilitation program in coronary heart disease patients: a prospective, monocentric and observational studyPaul Da Ros Vettoretto, Anne-Armelle Bouffart, Youna Gourronc, Anne-Charlotte Baron, Marie Gaumé, Florian Congnard, Bénédicte Noury-Desvaux, Pierre-Yves de Müllenheim https://hal.science/hal-04510104v4A prospective observational study examining changes in exercise capacity, physical activity, and motivation for physical activity 12 months after a cardiac rehabilitation programme in patients with coronary heart diseaseRecommended by Franco Milko Impellizzeri based on reviews by Géraldine Escriva-Boulley, Baraa Al-Khazraji and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Géraldine Escriva-Boulley, Baraa Al-Khazraji and 1 anonymous reviewer

Exercise capacity is recognised as a strong predictor of mortality and cardiovascular morbidity in both healthy individuals and patients with coronary heart disease (Novaković et al., 2022). Accordingly, exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation is recommended as an effective secondary preventive intervention (Task Force Members et al., 2016; Anderson et al., 2016). While earlier studies generally focused on changes in exercise capacity during or immediately after rehabilitation (Uddin et al., 2016), recent research has emphasised the importance of physical activity trajectories on mortality in patients with coronary heart disease (Gonzalez-Jaramillo et al., 2022). This highlights the need to understand changes in exercise capacity and physical activity following the rehabilitation phase. This study specifically explored changes in exercise capacity (assessed using the six-minute walking test) and physical activity (assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form) one year after a cardiac rehabilitation programme in patients with coronary heart disease. Additionally, the authors examined changes in motivation for physical activity over the 12 months following rehabilitation. Within the limitations of its observational and monocentric nature, the study presents important findings that can inform future research, generate hypotheses, and guide the design of targeted trials aimed at improving or maintaining exercise capacity and physical activity levels after rehabilitation. The exploration of potential barriers to physical activity 12 months after rehabilitation could inform strategies to increase participation in physical activity post-rehabilitation, thereby improving survival (Moholdt et al., 2018). This study is well-conducted and clearly presented. The authors' interpretation is balanced and consistent with the study's design and analysis. As noted by one of the reviewers, retention in cardiac rehabilitation studies is challenging, and the authors have done a commendable job in retaining participants. They have also addressed all the reviewers' concerns properly and accurately. I am pleased to recommend this preprint. References

- Novaković M, Novak T, Vižintin Cuderman T, Krevel B, Tasič J, Rajkovič U, Fras Z, Jug B. Exercise capacity improvement after cardiac rehabilitation following myocardial infarction and its association with long-term cardiovascular events. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2022;21(1):76-84. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvab015

- Task Force Members, Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts): Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23(11):NP1-NP96. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487316653709

- Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson DR, et al. Exercise-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation for Coronary Heart Disease: Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(1):1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.044

- Uddin J, Zwisler AD, Lewinter C, et al. Predictors of exercise capacity following exercise-based rehabilitation in patients with coronary heart disease and heart failure: A meta-regression analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23(7):683-693. https://doi.org/10.1177/204748731560431

- Gonzalez-Jaramillo N, Wilhelm M, Arango-Rivas AM, Gonzalez-Jaramillo V, Mesa-Vieira C, Minder B, Franco OH, Bano A. Systematic review of physical activity trajectories and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:1690-1700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.02.036

- Moholdt T, Lavie CJ, Nauman J. Sustained physical activity, not weight loss, associated with improved survival in coronary heart disease [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(13):1499. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.03.013]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(10):1094-1101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.01.011

- Da Ros Vettoretto P, Bouffart AA, Gourronc Y, Baron AC, Gaumé M, Congnard F, Noury-Desvaux B, de Müllenheim PY (2024) Change in exercise capacity, physical activity and motivation for physical activity at 12 months after a cardiac rehabilitation program in coronary heart disease patients: a prospective, monocentric and observational study. HAL, ver.3, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Health & Movement Sciences. https://hal.science/hal-04510104v3

| Change in exercise capacity, physical activity and motivation for physical activity at 12 months after a cardiac rehabilitation program in coronary heart disease patients: a prospective, monocentric and observational study | Paul Da Ros Vettoretto, Anne-Armelle Bouffart, Youna Gourronc, Anne-Charlotte Baron, Marie Gaumé, Florian Congnard, Bénédicte Noury-Desvaux, Pierre-Yves de Müllenheim | <p>Exercise capacity (EC) and physical activity (PA) are relevant predictors of mortality in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) but the CHD-specific long-term trajectories of these outcomes after a cardiac rehabilitation (CR) program are n... | Health & Disease, Physical Activity, Rehabilitation | Franco Milko Impellizzeri | 2024-03-22 10:59:07 | View | ||

25 Oct 2024

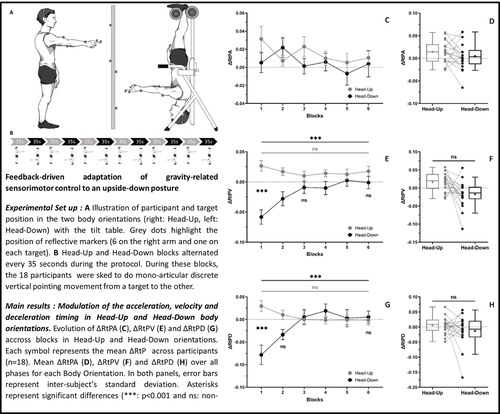

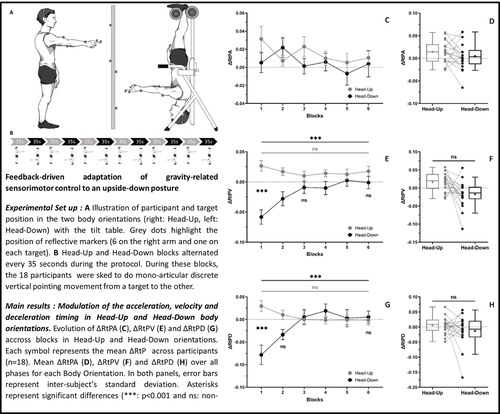

Feedback-driven adaptation of gravity-related sensorimotor control to an upside-down postureDenis Barbusse, Sarah Amoura, Jérémie Gaveau, Olivier White https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/D9JPFAn inverse gravity experiment supports the theory of an internal gravity model in the central nervous systemRecommended by Anne Koelewijn based on reviews by Jan Hondzinski and 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Jan Hondzinski and 3 anonymous reviewers

The study by Barbusse et al. (2024) investigated how motor control of arm movements is affected by reversed gravity. It is commonly assumed that the central nervous system contains an internal gravity model, and that this model is used to optimize movements to minimize effort under the influence of gravity (e.g., Berret et al., 2008). Previously, the effect of decreased and increased gravity was investigated, and it was shown that people were able to adapt to this novel environment in a matter of minutes or days (e.g., Gaveau et al., 2011). Therefore, the authors investigated the effect of inverse gravity on motor control of arm movements. In this study, an experiment was performed in which participants were placed in an inversion table and asked to perform as many pointing movements with their shoulder as possible in 12 blocks. In each block, the inversion table was placed either in the head-up or head-down position, and the position was switched every 35 seconds, starting from the head-up position. After 4 blocks, a 90 second break was taken. It was found that movement duration and amplitude did not significantly differ between both orientations. An analysis of the difference in time to peak acceleration, time to peak velocity, and time to peak deceleration between upward and downward movements revealed no significant difference for the peak acceleration, while for the peak velocity, the time difference was significantly smaller in the head-down than the head-up position, and for the peak deceleration, the time difference changed in the head-down position with the number of blocks, reaching a value more similar to the head-up (baseline) position. The time to peak acceleration did not reverse for the head-down position, which showed that the central nervous system is not able to take advantage of gravity when it is placed in a head-down position, since it does not take advantage of the “free” acceleration provided by gravity. A longer exposure to inverse gravity might allow the body to adapt and re-optimize its internal gravity model to the new situation. The time difference was significantly different for the deceleration, but not for acceleration, which indicates that the movement was adapted mainly by feedback control, but that feedforward control remained largely the same. This further supports the conclusion that the central nervous system had not yet adapted its internal gravity model, and that re-optimization starts with adapting feedback control (Izawa et al., 2008). An important limitation is the discomfort that is experienced in the head-down position, which not only changes gravity, but also created negative physiological responses. References Denis Barbusse, Sarah Amoura, Jérémie Gaveau, Olivier White (2024) Feedback-driven adaptation of gravity-related sensorimotor control to an upside-down posture. OSF preprints, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Health & Movement Sciences. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/D9JPF. Berret B, Darlot C, Jean F, Pozzo T, Papaxanthis C, Gauthier JP (2008) The inactivation principle: mathematical solutions minimizing the absolute work and biological implications for the planning of arm movements. PLoS computational biology, 4, e1000194. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000194 Gaveau J, Paizis C, Berret B, Pozzo T, Papaxanthis C (2011) Sensorimotor adaptation of point-to-point arm movements after spaceflight: the role of internal representation of gravity force in trajectory planning. Journal of Neurophysiology, 106, 620–629. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00081.2011 Izawa J, Rane T, Donchin O, Shadmehr R (2008) Motor adaptation as a process of reoptimization. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 28, 2883–2891. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5359-07.2008 | Feedback-driven adaptation of gravity-related sensorimotor control to an upside-down posture | Denis Barbusse, Sarah Amoura, Jérémie Gaveau, Olivier White | <p>The ability to move is a vital and essential feature of human existence. We are experts at producing a variety of movements and have refined their control through evolution. As gravity is a major feature of our every-day environment, we h... |  | Biomechanics, Sensorimotor Control | Anne Koelewijn | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2023-12-14 11:47:30 | View |

23 Sep 2024

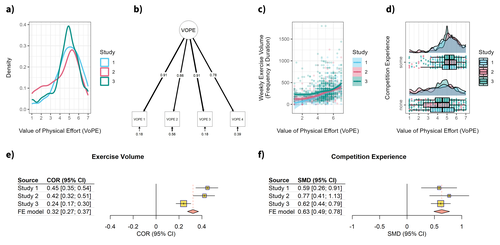

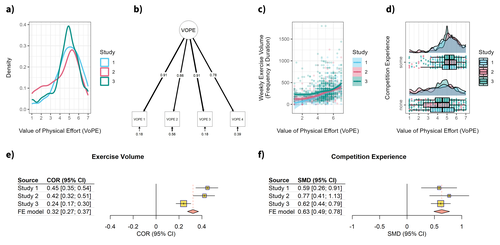

Development and validation of the Value of Physical Effort (VoPE) scaleMaik Bieleke, Johanna Stähler, Wanja Wolff, Julia Schüler https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/pqw26Capturing Individual Differences in the Valuation of Physical EffortRecommended by Boris Cheval based on reviews by Silvio Maltagliati and Erik Bijleveld based on reviews by Silvio Maltagliati and Erik Bijleveld

Physical effort has long been viewed as an aversive experience that people generally seek to avoid, giving rise to the so-called "law of least effort," which posits that, other things being equal, people tend to minimize effort when engaging in goal-directed tasks. This principle has recently been applied to physical activity behavior (Cheval & Boisgontier, 2021).

However, beyond this general view of physical effort as an aversive experience to be avoided, substantial individual differences in the valuation of physical effort have been observed. This suggests that some individuals may actually evaluate physical effort positively. Contrary to the law of least effort, these individuals may prefer behavioral alternatives that require more effort, all else being equal (Inzlicht et al., 2018). Until the development of the Physical Effort Scale (Cheval et al., 2024) and the present work by Bieleke et al. (2024), no formal scale existed to capture such individual differences in the valuation of physical effort. The primary goal of the present study was to design, develop, and validate such a scale. To achieve this goal, the authors conducted three independent studies (total N = 1,364) to establish the psychometric properties of the Value of Physical Effort (VoPE) scale (Bieleke et al., 2024). Across these studies, using both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs and a variety of statistical techniques (e.g., psychometric network analysis, elastic net regression), results indicated that the VoPE scale has robust associations with physical activity behaviors, strong test-retest reliability, and captures unique variance in predicting exercise behaviors. Taken together, these findings suggest that the VoPE scale is a valid and reliable measure of individual differences in the valuation of physical effort. References

Bieleke M, Stähler J, Wolff W, Schüler J. Development and validation of the Value of Physical Effort (VoPE) scale.PsyArXiv. 2023, version 5. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/pqw26. Peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Health and Movement Sciences. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.healthmovsci.100115 Cheval B, Boisgontier MP. The theory of effort minimization in physical activity. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2021;49(3):168-178. https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000252 Cheval B, Maltagliati S, Courvoisier DS, Marcora S, Boisgontier MP.Development and validation of the physical effort scale (PES). Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2024;72:102607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2024.102607 Inzlicht M, Shenhav A, Olivola CY. The effort paradox: effort is both costly and valued. Trends Cogn Sci. 2018;22(4):337-349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2018.01.007 | Development and validation of the Value of Physical Effort (VoPE) scale | Maik Bieleke, Johanna Stähler, Wanja Wolff, Julia Schüler | <p>Physical effort has instrumental value because it helps people attain their goals. Growing evidence suggests that people might also experience the exertion of effort itself as valuable. To test this idea, we developed and examined the 4-item Va... |  | Exercise & Sports Psychology, Physical Activity | Boris Cheval | Erik Bijleveld, Silvio Maltagliati | 2024-04-10 11:44:26 | View |

30 Aug 2024

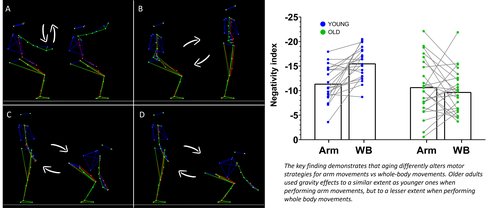

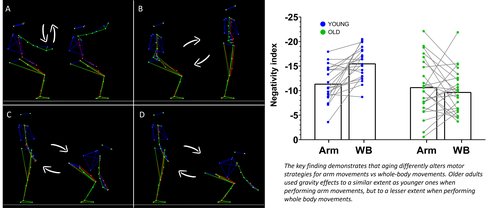

Comparing arm to whole-body motor control disambiguates age-related deterioration from compensationRobin Mathieu, Florian Chambellant, Elizabeth Thomas, Charalambos Papaxanthis, Pauline Hilt, Patrick Manckoundia, France Mourey, Jeremie Gaveau https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.16.576683Aging of upper-limb and whole-body movement efficiencyRecommended by Matthieu Boisgontier based on reviews by Florian Monjo, Pierre Morel, Zack van Allen and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Florian Monjo, Pierre Morel, Zack van Allen and 1 anonymous reviewer

This study by Mathieu et al. (2024) builds on previous computational research showing that human arm movements use gravity to save energy and be more efficient (Berret et al., 2008; Crevecoeur et al., 2009; Gaveau et al., 2014, 2021), as well as on experimental research showing that kinematic and electromyographic markers are directly related to this energetic efficiency (Gaveau et al., 2016). | Comparing arm to whole-body motor control disambiguates age-related deterioration from compensation | Robin Mathieu, Florian Chambellant, Elizabeth Thomas, Charalambos Papaxanthis, Pauline Hilt, Patrick Manckoundia, France Mourey, Jeremie Gaveau | <p>As the global population ages, it is crucial to understand sensorimotor compensation mechanisms. These mechanisms are thought to enable older adults to remain in good physical health, but despite important research efforts, they remain essentia... |  | Biomechanics, Sensorimotor Control | Matthieu Boisgontier | 2024-02-19 10:41:33 | View | |

05 Jul 2024

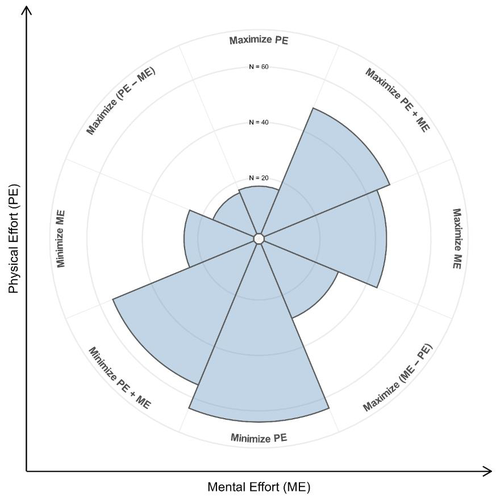

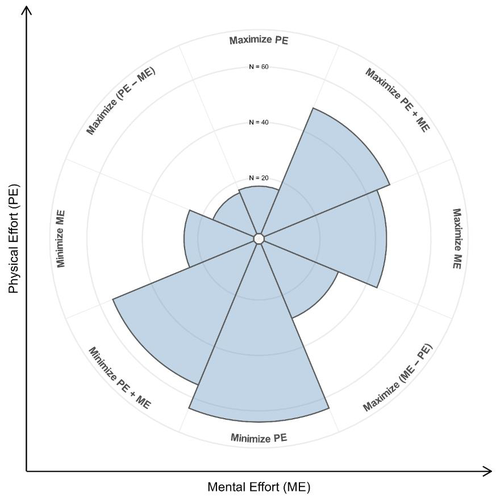

On the specifics of valuing effort: a developmental and a formalized perspective on preferences for mental and physical effortWanja Wolff, Johanna Stähler, Julia Schüler, Maik Bieleke https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ycvxwIs effort evaluation domain-specific or general?Recommended by Boris Cheval based on reviews by James Steele, Ines Pfeffer and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by James Steele, Ines Pfeffer and 1 anonymous reviewer

The law of least effort suggests that, certis paribus, people tend to exert as little effort as possible when engaged in a goal-directed task (Cheval & Boisgontier, 2021). At the same time, however, large interindividual differences in the processing of effort have been observed, suggesting that effort per se can sometimes be valued positively (Inzlicht et al., 2018). However, until the present study by Wolff et al. (2024), all previous studies had largely ignored whether these individual differences in the valuation of effort might depend on the context (mental versus physical), i.e., in layman's terms, we do not know whether people value any effort or whether these preferences are specific to the mental and/or physical domain. The aim of the present study (Wolff et al., 2024) was to answer this question on the basis of two independent studies. Study 1 (N = 39) used a binary decision task to measure preferences for allocating mental versus physical effort and showed that people differ markedly in their preferred allocation of effort. Crucially, a disposition to value mental effort (as assessed by the Need for Cognition Scale) was associated with a higher preference for mental effort, whereas a disposition to value physical effort (as assessed by the recently developed Value of Physical Effort Scale) was associated with a preference for physical effort. Study 2 (N = 300 students) confirmed the robustness of the findings and showed that the tendency to value mental effort was associated with better grades in math (but showed no evidence of such an association in sport), whereas the tendency to value physical effort was associated with better grades in sport (but showed no evidence of such an association in math). Furthermore, the study extended these findings by showing that valuing physical effort was associated with less boredom in sports, whereas valuing mental effort was associated with less boredom in math. In summary, the results of this research provide the first evidence suggesting that the valuation of effort is domain-specific rather than general. This finding paves the way for future research aimed at improving our understanding of the valuation of physical or mental effort. This article makes an important contribution to the knowledge of the key issues surrounding whether effort valuation is domain-specific or general. Since all reviewers have indicated that they are satisfied with the authors' revision, which accurately and comprehensively addresses the reviewers' and my comments, it is my pleasure to recommend this preprint. References

Cheval B, Boisgontier MP. The theory of effort minimization in physical activity. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2021;49(3):168-178. https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000252 Inzlicht M, Shenhav A, Olivola CY. The effort paradox: effort is both costly and valued. Trends Cogn Sci. 2018;22(4):337-349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2018.01.007

Wolff W, Stähler J, Schüler J, Bieleke M. On the specifics of valuing effort: a developmental and a formalized perspective on preferences for mental and physical effort. PsyArXiv, version 3. Peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Health and Movement Sciences.

https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ycvxw | On the specifics of valuing effort: a developmental and a formalized perspective on preferences for mental and physical effort | Wanja Wolff, Johanna Stähler, Julia Schüler, Maik Bieleke | <p>Effort is instrumental for goal pursuit. But its exertion is aversive and people tend to invest as little effort as possible. Contrary to this principle of least effort, research shows that effort is sometimes treated as if it was valuable in i... |  | Exercise & Sports Psychology, Physical Education | Boris Cheval | 2023-09-06 09:05:07 | View |

FOLLOW US

MANAGING BOARD

Matthieu Boisgontier (Representative)

Ségolène Guérin