Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers▲ | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

24 Aug 2023

Comparing habit-behaviour relationships for organised versus leisure time physical activityKaterina Newman, Cyril Forestier, Boris Cheval, Zackary Zenko, Margaux de Chanaleilles, Benjamin Gardner, Amanda L. Rebar https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/x5e9dHabit-behaviour relationships in organised and leisure-time physical activityRecommended by Eleftheria Giannouli based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersDespite public health campaigns, achieving recommended physical activity levels remains challenging. Investigating the factors influencing physical activity is essential for effective promotion. Habit strength is known to correlate with physical activity (Hagger, 2019), making habit formation a key intervention target. Newman et al. (2023) expand current knowledge on physical activity and habit strength. They investigate if habit strength and its association with behavior differ between organized and leisure-time physical activities. Given the broad definition of physical activity and individual differences in preferences, studying habit's influence on varied activities is crucial. The cross-sectional survey, spanning the UK, USA, Australia, and Switzerland, involves 120 young adults (mean age = 25) engaged in organized sports. Although self-report measures are used, excluding commuting and occupational activity, the study yields intriguing results: Authors find significant habit strength differences between organized sports and leisure-time activities, indicating potential distinctions in habit formation drivers. Investigating factors establishing habits in organized sports could inform broader interventions. Remarkably, the impact of habits on behavior is consistent across both activity types, suggesting a universal role of habits. Further analysis reveals stronger habit strength in team sports versus individual ones, with no behavior association difference. Diverse habit strength in organized versus leisure-time activities underscores the need for focused research. Understanding unique aspects of team sports that promote habituation can reshape interventions, aligning leisure activities with organized sports' characteristics. References Hagger, M. S. (2019). Habit and physical activity: Theoretical advances, practical implications, and agenda for future research. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42, 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.12.007 Newman, K., Forestier, C., Cheval, B., Zenko, Z., De Chanaleilles, M., Gardner, B., & Rebar, A. L. (2023). Comparing habit-behaviour relationships for organised versus leisure time physical activity. OSF Preprints, 1–11, version 4, peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Health & Movement Sciences. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/x5e9d

| Comparing habit-behaviour relationships for organised versus leisure time physical activity | Katerina Newman, Cyril Forestier, Boris Cheval, Zackary Zenko, Margaux de Chanaleilles, Benjamin Gardner, Amanda L. Rebar | <p>Evidence shows that people with strong physical activity habits tend to engage in more physical activity than those with weaker habits, but little is known about how habit influences specific types of physical activity. This study aimed to test... |  | Health & Disease, Physical Activity | Eleftheria Giannouli | 2023-03-01 08:59:18 | View | |

05 Jul 2024

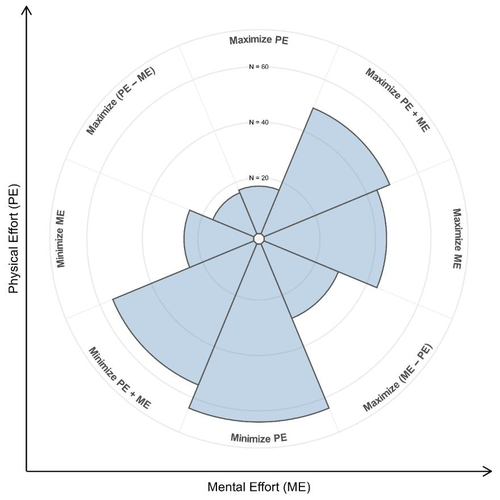

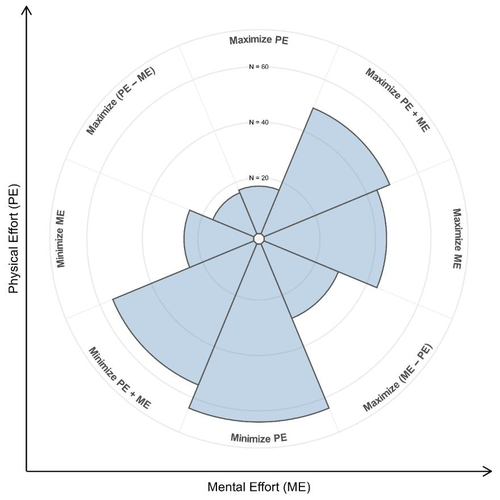

On the specifics of valuing effort: a developmental and a formalized perspective on preferences for mental and physical effortWanja Wolff, Johanna Stähler, Julia Schüler, Maik Bieleke https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ycvxwIs effort evaluation domain-specific or general?Recommended by Boris Cheval based on reviews by James Steele, Ines Pfeffer and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by James Steele, Ines Pfeffer and 1 anonymous reviewer

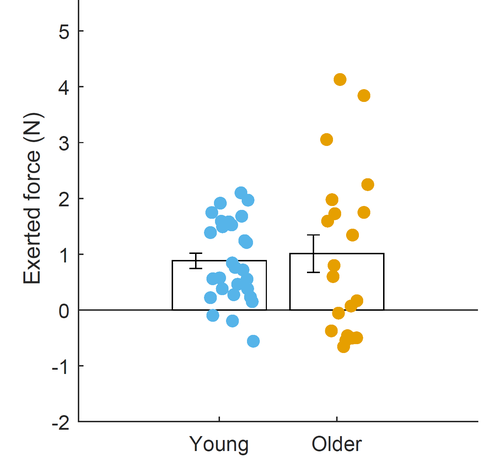

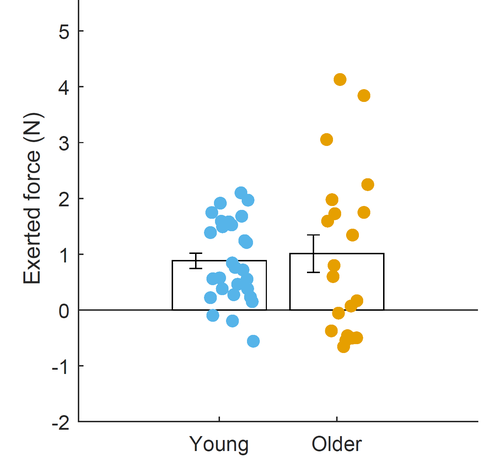

The law of least effort suggests that, certis paribus, people tend to exert as little effort as possible when engaged in a goal-directed task (Cheval & Boisgontier, 2021). At the same time, however, large interindividual differences in the processing of effort have been observed, suggesting that effort per se can sometimes be valued positively (Inzlicht et al., 2018). However, until the present study by Wolff et al. (2024), all previous studies had largely ignored whether these individual differences in the valuation of effort might depend on the context (mental versus physical), i.e., in layman's terms, we do not know whether people value any effort or whether these preferences are specific to the mental and/or physical domain. The aim of the present study (Wolff et al., 2024) was to answer this question on the basis of two independent studies. Study 1 (N = 39) used a binary decision task to measure preferences for allocating mental versus physical effort and showed that people differ markedly in their preferred allocation of effort. Crucially, a disposition to value mental effort (as assessed by the Need for Cognition Scale) was associated with a higher preference for mental effort, whereas a disposition to value physical effort (as assessed by the recently developed Value of Physical Effort Scale) was associated with a preference for physical effort. Study 2 (N = 300 students) confirmed the robustness of the findings and showed that the tendency to value mental effort was associated with better grades in math (but showed no evidence of such an association in sport), whereas the tendency to value physical effort was associated with better grades in sport (but showed no evidence of such an association in math). Furthermore, the study extended these findings by showing that valuing physical effort was associated with less boredom in sports, whereas valuing mental effort was associated with less boredom in math. In summary, the results of this research provide the first evidence suggesting that the valuation of effort is domain-specific rather than general. This finding paves the way for future research aimed at improving our understanding of the valuation of physical or mental effort. This article makes an important contribution to the knowledge of the key issues surrounding whether effort valuation is domain-specific or general. Since all reviewers have indicated that they are satisfied with the authors' revision, which accurately and comprehensively addresses the reviewers' and my comments, it is my pleasure to recommend this preprint. References

Cheval B, Boisgontier MP. The theory of effort minimization in physical activity. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2021;49(3):168-178. https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000252 Inzlicht M, Shenhav A, Olivola CY. The effort paradox: effort is both costly and valued. Trends Cogn Sci. 2018;22(4):337-349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2018.01.007

Wolff W, Stähler J, Schüler J, Bieleke M. On the specifics of valuing effort: a developmental and a formalized perspective on preferences for mental and physical effort. PsyArXiv, version 3. Peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Health and Movement Sciences.

https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ycvxw | On the specifics of valuing effort: a developmental and a formalized perspective on preferences for mental and physical effort | Wanja Wolff, Johanna Stähler, Julia Schüler, Maik Bieleke | <p>Effort is instrumental for goal pursuit. But its exertion is aversive and people tend to invest as little effort as possible. Contrary to this principle of least effort, research shows that effort is sometimes treated as if it was valuable in i... |  | Exercise & Sports Psychology, Physical Education | Boris Cheval | 2023-09-06 09:05:07 | View | |

18 Feb 2024

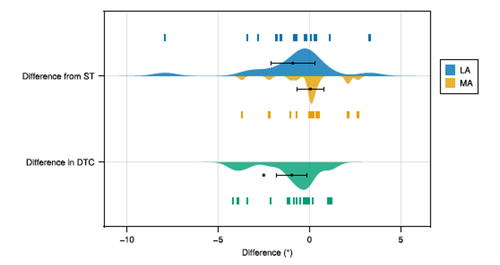

Interlimb coordination in Parkinson’s Disease is minimally affected by a visuospatial dual taskAllen Hill, Julie Nantel https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.15.500215A recommendation of ‘Interlimb coordination in Parkinson’s Disease is minimally affected by a visuospatial dual task’Recommended by Deepak Ravi based on reviews by Nicholas D'Cruz and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nicholas D'Cruz and 1 anonymous reviewer

Effective gait fundamentally requires spatial and temporal coordination of upper and lower limbs. Individuals with Parkinson’s disease (PD) often exhibit impaired coordination, leading to adverse events such as freezing of gait and falls (Plotnik et al. 2008). Despite their significance, the current literature lacks depth in our understanding of this characteristic, especially their adaptation to changing task demands and symptom laterality. Exploring these relationships may provide new insights into PD gait and facilitate the evaluation of potential treatments. With these objectives in mind, the present study conducted by Hill & Nantel (2024) includes 17 participants with mild to moderate PD and focuses on coordination within and between the more and less affected sides during both single and dual gait tasks. In the study, spatial coordination, assessed by range of motion, range of motion variability, and peak flexion for the shoulder and hip joints, was examined alongside temporal coordination, which was evaluated using the phase coordination index and variability of continuous relative phase. Their analysis reveals that, due to dual tasking, only the shoulder range of motion and peak flexion decreased within the least affected side, adding to the existing knowledge on arm swing impairments in early-stage PD (Navarro-López et al. 2022). However, no significant difference was observed between the more and less affected sides. Hip range of motion showed dual task-related differences between sides, while lower intralimb phase variability did not. The primary strength of the article lies in its attempt to systematically explore these differences in PD. As the authors pointed out, to interpret the clinical significance of these differences as well as the null findings on temporal coordination, it may be necessary to include a healthy control group or other comparison groups, such as individuals with severe PD. When interpreting these results, readers may also pay attention to the methodological choices, such as the patient-reported most affected side and the choice of dual task. Overall, the study will be of interest to researchers studying intra- and inter-limb coordination during gait in PD. References Plotnik, M., & Hausdorff, J. M. (2008). The role of gait rhythmicity and bilateral coordination of stepping in the pathophysiology of freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease. Movement disorders: official journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 23(S2), S444-S450. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.21984 Hill, A., & Nantel, J. (2024). Interlimb coordination in Parkinson’s Disease is minimally affected by a visuospatial dual task. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Health and Movement Science. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.15.500215 Navarro-Lopez, V., Fernandez-Vazquez, D., Molina-Rueda, F., Cuesta-Gomez, A., Garcia-Prados, P., del-Valle-Gratacos, M., & Carratala-Tejada, M. (2022). Arm-swing kinematics in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait & Posture, 98, 85-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2022.08.017 | Interlimb coordination in Parkinson’s Disease is minimally affected by a visuospatial dual task | Allen Hill, Julie Nantel | <p style="text-align: justify;">Parkinson’s disease (PD) leads to reduced spatial and temporal interlimb coordination during gait as well as reduced coordination in the upper or lower limbs. Multi-tasking when walking is common during real-world a... |  | Biomechanics, Health & Disease, Sensorimotor Control | Deepak Ravi | 2023-10-13 21:54:15 | View | |

06 Mar 2024

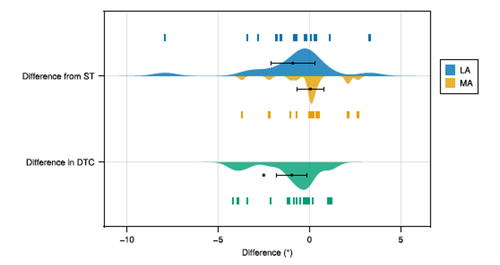

Not fleeting but lasting: Limited influence of aging on implicit adaptative motor learning and its short-term retentionPauline Hermans, Koen Vandevoorde, Jean-Jacques Orban de Xivry https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.30.555501Does aging affect implicit motor adaptation?Recommended by Rajiv Ranganathan based on reviews by Kevin Trewartha and Marit RuitenbergMotor adaptation to environmental perturbations (such as visuomotor rotations and force fields) is thought to be achieved through the interaction of implicit and explicit processes [1]. However, the extent to which these processes are affected by aging is unclear, partly because of differences in experimental protocols. In this paper, Hermans et al. [2] address the question of whether the implicit component of learning is affected in older adults.

Using a force-field adaptation paradigm, the authors examine implicit adaptation and spontaneous recovery in healthy young and older adults. Overall, the authors found that both total adaptation and implicit adaptation was not affected in older adults. They also found evidence that spontaneous recovery was associated with implicit adaptation, but was not affected in older adults.

These results are noteworthy because they challenge some prior work in the field [3], but are also consistent with results from other experimental paradigms [4]. A main strength of the current paper is the rigor applied to testing this question. The authors provide robust, converging evidence from multiple analyses and statistical methods, and control for confounds both statistically and experimentally.

Readers might want to note that this is a ‘conceptual’ replication of the previous study [3], and there are some potentially important differences in experimental details, which are clearly outlined. The sensitivity of the findings to such experimental parameters needs further testing. More broadly, these results highlight the need for greater understanding of how age differences observed in other motor learning tasks [5] are reflective of deficits in learning mechanisms.

References

1. Taylor, J. A., & Ivry, R. B. (2011). Flexible cognitive strategies during motor learning. PLoS computational biology, 7(3), e1001096. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001096

2. Hermans, P., Vandevoorde, K., & Orban de Xivry, J. J. (2024). Not fleeting but lasting: Limited influence of aging on implicit adaptative motor learning and its short-term retention. bioRxiv, ver.2, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Health & Movement Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.30.555501

3. Trewartha, K. M., Garcia, A., Wolpert, D. M., & Flanagan, J. R. (2014). Fast but fleeting: adaptive motor learning processes associated with aging and cognitive decline. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 34(40), 13411–13421. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1489-14.2014

4. Vandevoorde, K., & Orban de Xivry, J. J. (2019). Internal model recalibration does not deteriorate with age while motor adaptation does. Neurobiology of aging, 80, 138–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.03.020

5. Voelcker-Rehage, C. (2008). Motor-skill learning in older adults—a review of studies on age-related differences. European review of aging and physical activity 5, 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11556-008-0030-9

| Not fleeting but lasting: Limited influence of aging on implicit adaptative motor learning and its short-term retention | Pauline Hermans, Koen Vandevoorde, Jean-Jacques Orban de Xivry | <p>In motor adaptation, learning is thought to rely on a combination of several processes. Two of these are implicit learning (incidental updating of the sensory prediction error) and explicit learning (intentional adjustment to reduce target erro... |  | Sensorimotor Control | Rajiv Ranganathan | Marit Ruitenberg, Kevin Trewartha | 2023-09-02 13:23:44 | View |

15 Jun 2024

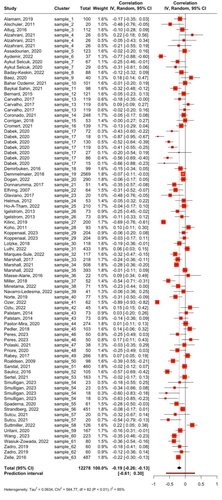

Kinesiophobia and physical activity: A systematic review and meta-analysisGoubran M, Farajzadeh A, Lahart IM, Bilodeau M, Boisgontier MP https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.17.23294240Evidence of the Association between Kinesiophobia and Physical InactivityRecommended by Jasmin Hutchinson based on reviews by Paquito Bernard and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Paquito Bernard and 1 anonymous reviewer

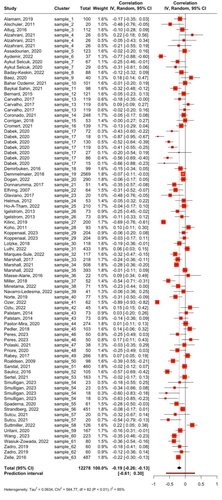

This article (Goubran et al., 2024) presents a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis examining the relationship between kinesiophobia and physical activity. The inclusion of multiple health conditions and diverse measures of physical activity and kinesiophobia provides a broad perspective on the issue. Kinesiophobia (i.e., an excessive, irrational, and debilitating fear of movement) is thought to contribute to negative affective associations towards physical activity and avoidance behaviors, leading to decreased engagement in physical activity. Thus, the relationship between kinesiophobia and physical activity merits further investigation, particularly in health conditions where physical activity has a preventative and/or therapeutic role. The results of this meta-analysis (k = 83, n = 12,278) indicate a small-to-moderate negative correlation between kinesiophobia and physical activity (r = −0.19; 95% CI: −0.26 to −0.13; I2 = 85.5%; p < 0.0001.) Substantial heterogeneity and publication bias were noted, but p-curve analysis suggested true effects. Notably, this finding was consistent across studies using both self-report and objective device-based measures, and there was no evidence of a moderating effect of different measurement instruments or physical activity outcomes. Subgroup analyses revealed that the negative association between kinesiophobia and physical activity is significant in patients with cardiac, rheumatologic, neurologic, or pulmonary conditions but not in those with chronic or acute pain. This latter finding underscores the need to distinguish kinesiophobia from pain. Understanding that the fear of pain, injury, or aggravating an underlying condition, rather than actual pain, is associated with physical inactivity is important to consider when developing interventions to promote physical activity. Tailored interventions that address kinesiophobia specific to different health conditions could enhance physical activity levels and improve health outcomes. Further research is needed to explore the mechanisms underlying kinesiophobia and evaluate the efficacy of targeted interventions to mitigate its impact. This article makes an important contribution to our understanding of the relationship between kinesiophobia and physical activity. It provides evidence that fear of movement can be a barrier to physical activity in certain health conditions and highlights the need for condition-specific approaches to address this issue. This work is highly relevant for clinicians, researchers, and public health policymakers aiming to improve physical activity levels and overall health outcomes in a variety of populations.

References Goubran, M., Farajzadeh, A., Lahart, I.M., Bilodeau, M. & Boisgontier, M.P. (2024). Physical activity and kinesiophobia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. MedRxiv, version. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Health and Movement Science. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.17.23294240 | Kinesiophobia and physical activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis | Goubran M, Farajzadeh A, Lahart IM, Bilodeau M, Boisgontier MP | <p><strong>Objective. </strong>Physical activity contributes to the primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of multiple diseases. However, in some patients, an excessive, irrational, and debilitating fear of movement (i.e., kinesiophobia) is t... |  | Exercise & Sports Psychology, Health & Disease, Physical Activity, Rehabilitation | Jasmin Hutchinson | Paquito Bernard | 2023-08-21 07:07:46 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Matthieu Boisgontier

Ségolène Guérin

Jennifer O’Neil

Leonardo Peyré-Tartaruga